Banking’s New Race: Using AI to Steal Your Rival’s Best Customers

by Yannis Larios

European banks and payment providers are entering a phase of competition that is less about financial products and balance sheet scale, and more about who can read the market’s intent signals fastest. Open banking, real-time data and increasingly capable AI models have combined to make customer defection a continuous process rather than an occasional event. Loyalty built on inertia is fading.

The numbers are not subtle. J.D. Power finds that only 46% of retail bank customers in the US are certain they will stay with their current bank, with 13% explicitly planning to switch in the next 12 months. In Europe, open-banking and switching initiatives have made movement easier still. A 2023 McKinsey survey of small businesses – historically viewed as “sticky” – reported that 41% were likely to change their primary bank within a year, while actual switching more than doubled compared with previous periods.

At the same time, digital insurgents and neobanks are treating this fluidity as opportunity rather than risk. Revolut’s customer base grew 38% in 2024 to 52.5 million, a rate of expansion that most banks can no longer contemplate.

Those customers are not necessarily new to the financial system; they are coming from somewhere else

In that context, it is no longer sufficient for banks to deploy AI simply to protect their existing base. European financial institutions need to complement their defensive efforts with a more uncomfortable idea: using AI systematically to identify when other banks’ customers are in play, and to move quickly to win them.

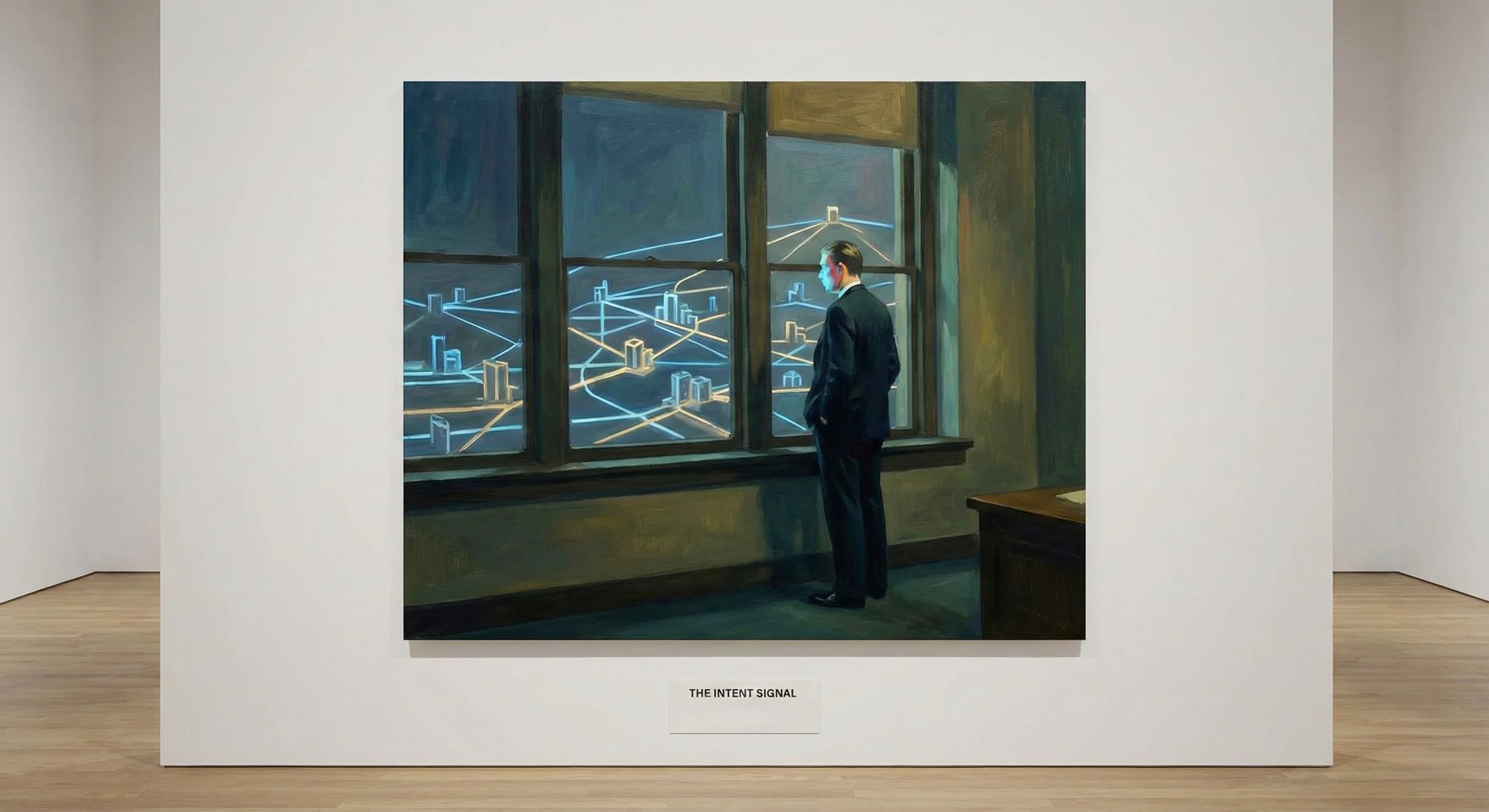

The trigger concept I am introducing here is the "money-in-motion" moment – those short windows when a competitor’s client is changing behaviour, reacting to a price move or signalling dissatisfaction. These moments are becoming observable at scale. The question is who chooses to act on them to win the customer.

The Strategic Shift - From Castle Defence to Active Raids

Facing these headwinds, most banks default to defensive plays – improving service to retain customers, matching competitors’ rates belatedly, or hoping brand heritage will prevail. This is conventional wisdom, but it’s no longer enough. The contrarian strategic shift is to go offense: leverage AI not just to fortify your own base, but to attack competitors’ bases and grab disaffected customers before they churn elsewhere. Instead of viewing “own-churn” as a problem to mitigate, treat it as an opportunity to exploit – but on your rivals’ turf.

This requires reframing AI’s role. Traditionally, banks used analytics to predict and prevent their customer churn (a reactive posture). The new approach is proactive and predatory: scanning the market for “money-in-motion” signals and acting on them in real time.

Individually, such events are unremarkable but in aggregate, they form a pattern. A large deposit arrives into a low-yield account and then sits idle. A mortgage payment jumps after a rate reset. A current account incurs new or higher fees. A client who has never used a fintech app suddenly links their cards to one. In a world of "money in motion", these are live signals that a customer could be open to changing provider. With open banking APIs and data partnerships, banks can increasingly detect such triggers across the ecosystem. Progressive players realize that “excess deposits and accounts are in motion, and banks that move fastest will capture them”

The cultural shift required by banks is to treat these signals as targets for action, not merely as background market intelligence.

The contrarian claim here is bold: Banks should deliberately target and poach competitors’ customers at their moment of “weakness”, guided by AI insights. This is a mindset shift from the old etiquette of competing quietly and focusing only on one’s own P&L. In telecoms, carriers have long engaged in this kind of sniping – for instance, using number-porting requests or contract expirations as cues to swoop in with a win-back offer, cutting churn by double-digits. Now, AI lets banks do similar, but far more surgically. Imagine getting an alert that Rival Bank X’s prized client (with €100K in deposits) just had an unpleasant fee or has moved €50K to a brokerage – and within hours your system generates a personalized outreach offering a higher savings rate or free wealth advisory to entice them over. This “always-on hunter” stance, powered by algorithms, turns your competitor’s customer dissatisfaction into your growth channel.

Strategically, this is contrarian because banks have historically been timid about aggressive client acquisition, especially targeting specific named competitors. But times have changed. As one 2025 banking outlook noted, “competitive forces are changing more rapidly than ever…More money in motion, lower switching costs…are converging”. Leaders will capitalize on this flux.

Just as Amazon seizes every chance to win over retail customers with algorithmically timed offers, banks must adopt a similar ruthless commercial mindset. Early adopters of this tactic can quickly widen the gap between themselves and slower-moving peers – a pattern seen in past downturns where bold investments in capability led to outsized advantage. In summary, the strategic shift is: don’t just play defense managing your churn – use AI to play offense and amplify

Lessons From Sectors That Moved First

Other industries offer a preview of what an AI-enabled, offensive acquisition playbook looks like in practice.

Telecoms were early adopters of churn modelling. AT&T, for example, has reported reducing millennial customer turnover by around 30% by using AI-driven segmentation to tailor retention programmes. Another operator cut churn by roughly 15% after reorganising customers into behaviour-based segments and personalising outreach. The important point is not the precise percentages, but the operating rhythm: models produce a ranked list of at-risk customers, and the organisation is conditioned to respond within hours, not months.

Retail and media have gone a step further. Netflix’s recommendation engine is estimated to save the company about $1bn a year by lowering churn through better content suggestions. Starbucks has shown that AI-driven, gamified offers in its mobile app can triple campaign performance and lead to a threefold increase in incremental spend among targeted customers. Here, AI does not simply label customers; it interferes, deliberately, in their next decision.

In B2B software, providers of “intent data” track which companies are researching certain topics, comparing tools or undergoing executive change. Those signals are then fed directly to sales teams. Several banks have begun to copy this approach in commercial banking: one leading European institution reports that relationship managers doubled their conversion rates when they shifted from cold prospecting to AI-generated lists of businesses exhibiting relevant “trigger events”.

Closer to home, European fintechs have shown how open banking can be turned from compliance obligation into competitive weapon. In 2024, bunq partnered with Mastercard’s open banking platform, allowing its 12.5 million customers to aggregate accounts from other banks inside the bunq app. Its AI assistant, “Finn”, analyses spending and balances across all linked accounts, not just bunq’s own. Within two weeks of launch, the bank saw a 40% per cent increase in engagement among users who connected external accounts. Once those external balances, fees and patterns are visible, it becomes straightforward to prompt a customer to move idle savings or fee-heavy accounts across.

Some incumbent banks are also experimenting. Santander and others have announced partnerships with AI specialists, including foundation-model providers, with the stated aim of sharpening data-driven marketing and anticipating customer needs more precisely. The details vary, but the direction of travel is consistent: use AI to make sense of increasingly rich data, then react before competitors do.

Even in the conservative world of aviation, the principle holds. Status-match offers are a direct attempt to entice the most profitable customers of a rival, while AI-enabled forecasting is now used to identify premium passengers at risk of downgrading their travel and to intervene before they decide. Banks do not need to copy airlines’ loyalty economics, but they should pay attention to the underlying mindset: in a mature market, growth increasingly comes from persuading someone else’s “good customer” to become yours.

What an offensive playbook could look like in banking

Translating these lessons into a European banking or payments context does not require an overhaul of the entire institution. However, it does demand clarity about ownership, data and decision-making.

The first requirement is strategic ownership. A “money-in-motion” agenda cannot be buried several levels down inside marketing or data science. It needs a senior sponsor – typically a Chief Commercial or Growth Officer – with a mandate to treat competitor churn as a distinct growth engine. That sponsor will convene a small cross-functional team, combining analytics, product and front-line expertise, whose task is to produce a recurring pipeline of actionable opportunities: well-targeted prospects, with clear economic rationale, where the bank can plausibly offer a better deal.

The second requirement is what might be termed a signal layer. Open banking data, when customers consent to sharing it, can reveal balances, transaction flows and payment patterns at other institutions. Credit-bureau triggers, public information on fee changes or outages, and the bank’s own record of lost deals all add to the picture. The aim is not omniscience. It is to define a manageable set of triggers that reliably indicate when a customer at another institution is both dissatisfied and economically attractive.

On top of that signal layer, the bank needs an AI stack focused on decisions, not just insight. Propensity models rank prospects by likelihood to respond if approached. Event-based models connect specific patterns – a large tax refund landing in a low-yield account, for instance – to specific actions, such as a savings or investment proposal. “Next best action” engines assemble the right product, pricing and channel into a concrete recommendation. Crucially, these outputs must flow directly into the same tools that bankers and digital channels already use. A ranked list of prospects that lives in a separate analytics portal will add little value. A list that appears in a relationship manager’s daily workbench, with context and suggested script, changes behaviour.

The final requirement is a willingness to test and scale. A serious institution does not need a continent-wide programme to begin! A single segment – for example, high-income individuals with visible external low-yield savings, or SMEs whose acquiring volumes suggest dissatisfaction with their PSP – is enough for a disciplined 90-day pilot. If the combination of signal layer, models and frontline execution cannot improve conversion and economics in that narrow slice, it is better to discover that early and adapt the approach than to roll out theatrically and learn nothing.

The governance questions for Boards

For Banks Boards, this more aggressive posture raises three classes of question.

The first concerns data, privacy and fairness. European regulation on data protection and open banking is explicit about consent and purpose. Using external account information to offer a customer a genuinely better product is one thing; using opaque profiling to target vulnerable groups is quite another. Boards will need assurance that any money-in-motion programme is designed with clear consent journeys, explainable models and regular audits of outcomes. They should be asking legal and compliance teams not only “is this allowed?” but “would we be comfortable if this appeared on the front page?”.

The second is strategic. If fintechs, neobanks and a subset of incumbents adopt this kind of offensive acquisition playbook, then institutions that do not will, by definition, become the source of other people’s growth. In markets where switching is becoming easier and data richer, deciding not to participate is not a neutral choice; it is a decision to subsidise more agile competitors. Boards need to be explicit about whether they accept that outcome, and if not, what tempo and scale of response they expect from management.

The third is organisational. Money-in-motion strategies only work if the institution can act at something closer to real-time speed. If it takes three committees and a quarter to approve a simple targeted offer, many of the potential gains will evaporate. Boards should therefore be less impressed by AI slideware and more interested in whether decision rights, incentives and technology plumbing have been adjusted to allow timely action when signals appear.

From Drift to Deliberate Capture

The European banking market is unlikely to become less competitive in the coming decade. As AI models improve, data becomes more granular and customers more mobile, the ability to recognise when a valuable client is “in motion” will become a core commercial capability, not an optional curiosity.

The institutions that succeed will be those that combine the discipline of banking – prudence, compliance, long-term stewardship – with a more candid view of competition. They will still invest in retaining their own clients, but they will also make a habit of asking a sharper question: whose best customers are there, in the data, telling us they are unhappy – and what are we prepared to do about it?

For boards and executive teams, the choice is not between “aggressive” and “polite”. It is between shaping this new race, or discovering, slowly and quietly, that their most profitable customers have been won over by someone who was paying closer attention.

If this resonates, please consider subscribing to “The Next Agenda” newsletter in Linkedin. For briefings or board-level discussions, feel free to reach out to me; Independent Non-Executive Director dialogues welcomed where my expertise adds value.